Who cares about Heinrich Müller anymore?

When and where did Heinrich Müller die? Who was Heinrich Müller?

The latter question is easier to answer than the first. Müller was a leading figure in the Holo-caust, Adolf Eichmann's immediate superior. Unlike Eichmann and many of his peers in the SS and Gestapo, Müller was never brought to justice.

Almost all the top Nazis were known for their odd interests and other idiosyncrasies. Was Müller a vegetarian like Hitler? No, he wasn't. A drug addict like Göring? No, he wasn't. A talent-ed musician like Heydrich? No, he wasn't. Loved to be the centre of attention like Goebbels? Ab-solutely not. Quite the contrary! Rather seems to have avoided being photographed. Lounge lion and madman in various uniforms like Göring? Not so much. Fascinated by racial biology like Himmler? Was not. Fervent anti-Semite? Probably no more so than many Catholic Bavarians of the time. Was he a family man who put his wife, home and children first? Absolutely not. Reli-gious? Yes, a devout Catholic. Communist hater? Yes, intensely. Was he a sadist who liked to torture his victims? Possibly, but he is more known for his prolonged harsh interrogations. Was he even a devout Nazi? Very uncertain.

His relative anonymity and mundanity also apply to his name. The most powerful Nazis are all known by their surnames, Hitler, Göring, Goebbels, Himmler, Heydrich, etc., but Müller has had to be called Gestapo-Müller by posterity, to distinguish him from all the other Müllers in Germa-ny at the time. There was even another SS general with the same first and last name.

The family belonged to the lower middle class in Munich; the father was a simple police of-ficer, the family very Catholic. The boy, born in 1900, received an education in keeping with his social environment: no grammar school, but public school and workshop training for a very mod-ern profession: aircraft mechanic. Like many German boys at the time, Heinrich volunteered for service at the age of 17. He joined the Royal Bavarian Armed Forces.

The step from airplane fitter to pilot was probably not so big during the childhood of aviation and during the burning war, and as a teenage aviator he must have been very successful. After the war ended, he was promoted, but without higher education he became no more than a non-commissioned officer. By then he had also been decorated several times.

The post-World War I period in Bavaria was very turbulent, and for a short time it was even a Socialist Council Republic. Müller probably sympathized with the reactionary Free Corps. He was later said to have been a supporter of the BVP, a Catholic party that advocated the special status of Bavaria in Germany. Himmler also supported this party but abandoned it in 1923.

During the 1920s, Munich, the capital of Bavaria, became a center for all kinds of reactionary and radical right-wing groups. During these years, Müller worked for the Munich police. His ca-reer was successful; he made a name for himself as an energetic monitor of communist groups. However, he was not a Nazi: he stood for Bavaria and used tough measures against all kinds of extremists. Müller thus intervened forcefully not only against Bolsheviks but also against Nazi troublemakers and coup-makers. He is also said to have spoken disparagingly of Hitler, like an immigrant unemployed house painter. He was outspoken against the Nazis both during the Beer Hall Putsch of 1923 and the seizure of power in 1933. All this, of course, led to him gaining op-ponents within the NSDAP.

But paradoxically, the Nazi takeover led to his career taking off in a remarkable way. Because when the Nazis took control of Germany, they began a process of Gleichschaltung, or ’equaliza-tion’, including the many local police forces in the Reich.

And when Reinhard Heydrich (1904-1942) became the head of the Gestapo in the whole Reich in 1934, he made the energetic Müller his second-in-command. In less than two years, Müller had risen from a mid-level post in the Bavarian police to a top position in the German Reich! His pa-tron Heydrich thus overlooked Müller's political past and had an eye for his great capacity and adaptability.

Müller was also given a high rank in the SS, perhaps because the SS was formally superior to the Gestapo. But the hyper-Nazi ideology of the SS was probably quite alien to the Catholic Ba-varian. His rapid career shows that the NSDAP party book was not always so important; Müller did not join the party until 1939. When Heydrich was assassinated outside Prague in 1942, Müller became head of the Gestapo in Germany and more.

During his time in the Gestapo, Müller became one of those ultimately responsible for a series of crimes of unprecedented scale, such as the Kristallnacht in 1938, the Wannsee decisions in 1942 and the implementation of the extermination of the Jews.

When and where did Heinrich Müller die?

Even before the collapse of Germany in the spring of 1945, the Anglo-American counter-espionage service (CI War Room) had taken an interest in all top Nazis. They were to be cap-tured, interrogated and tried. This was quite successful; many were discovered, many were con-victed and some committed suicide. However, the Gestapo top people proved elusive for a long time. Several were eventually tracked down, but never Müller.

As late as the end of June 1945, the Anglo-American Nazi hunters believed that Müller was still alive in Berlin, and not hiding in the Bavarian Alps like many others. An aggravating factor in the search for him was that he had such a common name; one of these was also an SS general.

Many rumors abounded about his fate but none of them led anywhere. In 1947, the Western Allies searched the house of Müller's mistress, but there was no indication that the wanted man was still alive. He was now presumed dead, which was a liberating assessment when the search had failed completely.

But the question whether he was dead or not remained for decades. Rumors surfaced that he had been seen here and there in the world. The most bizarre rumor was that he had become a high police chief in Albania.

The question of his whereabouts came to the fore in 1960 when Adolf Eichmann was put on trial in Israel. He claimed that Müller was still alive. The following year, the West German police also became involved, mainly with surveillance and searches of the family, the mistress and a sec-retary. Were there letters or other traces of contact? Nothing - nothing. Absolutely nothing.

It was now established that Müller had been in Hitler's bunker as late as the evening of May 1, together with his associate Christian Scholz. Müller is said to have declined the offer of an escape attempt, but also to have said that he had no plans to let the Russians take him prisoner. These statements may indicate that he was planning suicide or a separate breakout and escape.

An odd German report that Müller had been seen in Himmler's company in Schleswig Hol-stein several days after the fall of Berlin could not be followed up. Claims that he had died in Ber-lin during the collapse in May 1945 accumulated over the years. The search, which had long fo-cused on the living Müller, now concentrated on the search for his dead body.

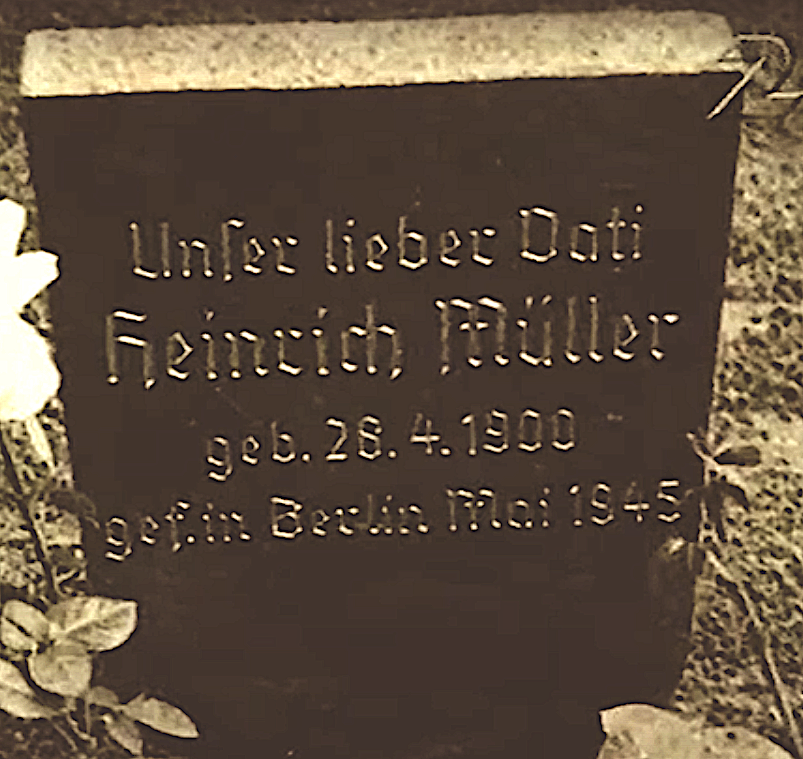

The search essentially followed three stories. The earliest came from a gravedigger in Berlin. He reported that the dead Müller had been taken from the Gestapo headquarters at Prinz Albert-strasse, and that the body had been buried in a cemetery at Lilienthalstrasse in the Neukölln dis-trict. This statement seemed to be supported by the fact that there was a gravestone there with the inscription:” Unser lieber Vati Heinrich Müller geb. 28.4 1900 gef. in Berlin Mai 1945”, i.e. roughly:” Our dear father/dad Heinrich Müller born in 4/28 1900 fallen in Berlin May 1945”.

The wording suggests that it is the children of the marriage, Reinhard (1927) and Elisabeth Müller (1936), who had the stone erected. This sounds quite normal, children want to honor their father, although the word” fallen” may sound very positive for this particular father. To be on the safe side, the West German police opened the grave in 1963, and indeed found body parts, but of three different people, and no parts that could be attributed to Müller.

What purpose could there be in carrying out such a burial with an expensive stone? Presuma-bly, they wanted to reassure the world that the person whose name was on the stone is dead.

Why would you want that? Probably because they are alive.

It is also rather uncertain whether Müller's two children by marriage were so fond of their” Va-ti”, who abandoned them and their mother for a mistress as early as 1939.

A second clue came in a roundabout way from the Soviets: a story that Russian soldiers had found Müller with his identity papers intact in the subway a few blocks from Hitler's Reich Chan-cellery. The body had a bullet through the head, possibly suicide. Müller was then buried in a mass grave in the old Jewish cemetery at Grosse Hamburgerstrasse in the Soviet zone.

A third story came from a German who worked on mass graves in the summer of 1945. He had seen an SS general in uniform and found him in the garden of the Reich Chancellery. The body had a large wound in the back. All medals and decorations were missing, but Müller's identi-fication documents were present. The body was buried in the cemetery at Grosse Hamburger-strasse. - The three stories seem difficult to reconcile into something convincing.

Further mystifying elements of Müller's disappearance: his awards, medals and identification documents are said to have turned up in 1957 and been transferred to his family, but never thor-oughly examined. And the gravestone from Lilienthalstrasse was bought in 1963 by an anony-mous woman.

Nowadays, Müller has been officially declared dead for many years. Most researchers believe that his body is probably in the mass grave in the Old Jewish Cemetery. But Jewish rules do not allow searching for the body.

A clue from Norway

After all this searching and speculating, which has led to no proof, only an official declaration of death, a clue from Norway may shed some light on the fate of the Gestapo. This clue not only sheds new light on the case, but also adds a human, existential dimension, because it deals with the search for a father, in this case a daughter's search for a father she never met.

This daughter, of course, growing up in Norway, had long wondered about her father and had done some research. By chance, in the 1990s, she met SVT's Lars Weldeborn (b. 1952), who was captivated by her story: a living daughter of the Gestapo's supreme leader, the mysterious Hein-rich Müller! After a lot of preparation and the green light from SVT's management, a reporting team was formed to follow the daughter's journey to find the truth about her father.

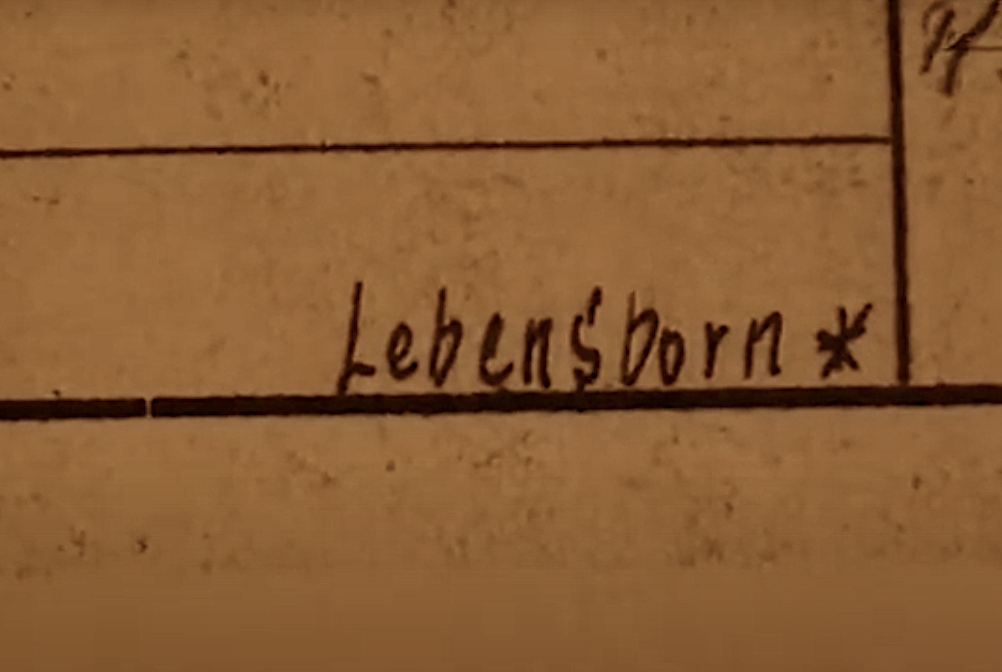

The documentary shows her contacts with various archives and people in Germany. In the Bundesarchiv's archives of SS officers, there is a dossier on Heinrich Müller with the note that he had a child in the care of the Lebensborn organization. This was an SS organization for the care of so-called Aryan children with German fathers. The entry in Müller's file unfortunately says nothing about where this child would have been born. But the note is supported by a record in a Norwegian hospital that Heinrich Müller was the father of a daughter born in June 1944.

Knowing from previous research that her father was a devout Catholic, the daughter was drawn to Rome, where, as is well known, several influential Catholics helped many Nazis escape after the war via the so-called Rat Line.

In Rome, she simply called the Vatican and requested information about her father. His name and existence seemed to be known (!) and she was put through to church history giant Erwin Gatz (1933-2011) who promised to give her information.

After a few days, she receives an envelope with a couple of photocopies from a printed book, but no covering letter. The copies hardly correspond to what the daughter had expected, not a word about any Müller. When she calls a second time to ask Gatz to explain what he meant, Gatz rejects her, he wants nothing more to do with her.

Instead, the photocopies are about a man called Hudal. Who was this Hudal, who does not appear in the literature on Gestapo-Müller?

Who was Hudal?

Hudal was a man of many names, many titles and many slightly varying opinions. His name was Alois Karl Hudal, sometimes called Luigi. He was from Graz (1885-1963), was ordained a priest, became a Doctor of Theology, first specializing in the Orthodox Churches, then a second time specializing in the Old Testament. He did the latter at the Austrian seminary of Santa Maria dell’ Anima in Rome, which became his base. He received the title of professor in Graz; in 1933 he was also appointed titular bishop.

In 1937 he became the rector of the seminary in Rome and tried to make it a German-speaking cultural center in Rome. In the same year, he published a highly acclaimed book, Die Grundlagen des Nationalsozialismus, in which he argued for the interweaving of Catholicism and Na-zism.

The book was reverently dedicated to Hitler, and Hudal was jokingly nicknamed the Brown Bishop. It was important for the Church to capitalize on the good aspects of Nazism. His main idea was that Catholicism and National Socialism should jointly fight Marxism and Com-munism, or Bolshevism as it was called at the time. However, he distanced himself from Nazi atheism and neo-paganism. He received strong support for his ideas.

But his influence, which had hitherto been steadily growing, reached a clear turning point the following year. Hudal vigorously promoted Austria's accession to the German Reich. His views put an end to both his career and his influence. The Catholic Church in general was not at all in favor of the idea. The Vatican was completely dominated by Italians who would have preferred Austria to remain what it was in 1938, an arch-Catholic and fascist state. Neither Mussolini nor the Italian government was attracted by the change.

Thus, although Hudal is incriminated by his support for German Nazism, in Rome in 1943-1944 he helped a few individuals fleeing the Nazis, including two New Zealanders; he may also have contributed to the sparing of 1 000 of Rome's Jews in the final stages of the war. Whether he did this out of the goodness of his heart or with calculation is impossible to say. Although he was a strong anti-Semite, he does not seem to have shared the Nazis' supposedly scientific view of the Jews as a biological race that had to be exterminated. For example, he is said to have spoken out against the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, which defined degrees of Jewishness.

After the war, he naturally lost all official prestige, but at the same time became a central figure in the so-called Rat Line, the Catholic Church's secret aid organization for Nazi and fascist war criminals. The Red Cross and Caritas also participated in this work. Among the hundreds of Na-zis Hudal directly or indirectly helped were the infamous Barbie, Eichmann and Mengele. In his memoirs, written in 1962 but not published until 1976, Hudal himself declares that he helped sev-eral “so-called war criminals”, and this out of pure human love.

But he remained rector of the Anima seminary in Rome until 1952. He died in 1963 and was given a stately grave in a cemetery for German-speaking Catholics, Campo Santo Teutonico in-side the walls of Vatican City.

It was documents about this strange semi-Nazi Bishop Hudal that Müller's daughter received from the Vatican historian Erwin Gatz, when she had asked about her father Heinrich Müller.

The photocopies not only told the story of Hudal's life, but also described his magnificent tomb. In it also rested his mother and some other people connected to the Anima seminary. But no Heinrich Müller. When his daughter tries to get an explanation, she is - as already mentioned - spurned by Gatz.

Who was Franz Andreas Kaminski?

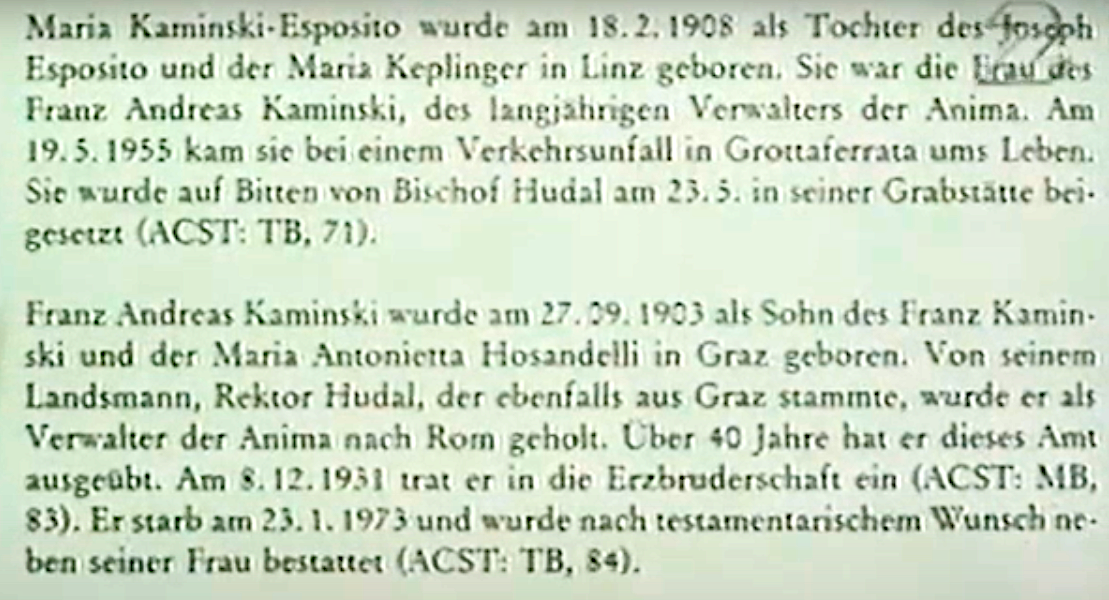

But the daughter and the SVT team do not let go of the clue in the photocopies, and attention is focused on a Franz Andreas Kaminski in Hudal's grave. He is said to have been born on 23.09.1903 in Graz, Austria; died in Rome on 23.01.1973. He is also said to have been administra-tor (Verwalter) of the Anima seminary for more than 40 years, i.e. before 1933. His wife also rest-ed there.

To confirm the information about the Kaminskis, Müller's daughter contacted all possible au-thorities in Austria. But these people are not to be found in the archives, neither born, baptized, nor married. It is therefore likely that their names are cover names for other persons.

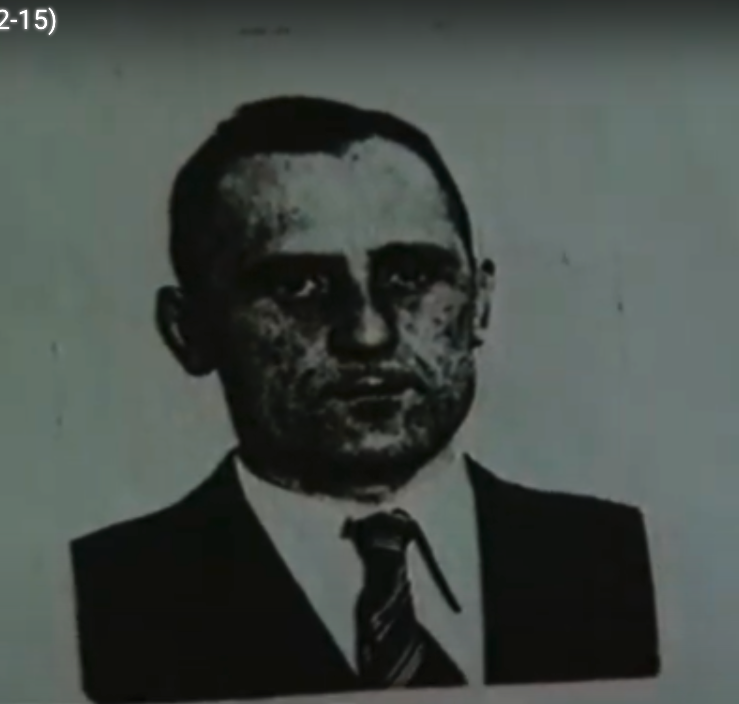

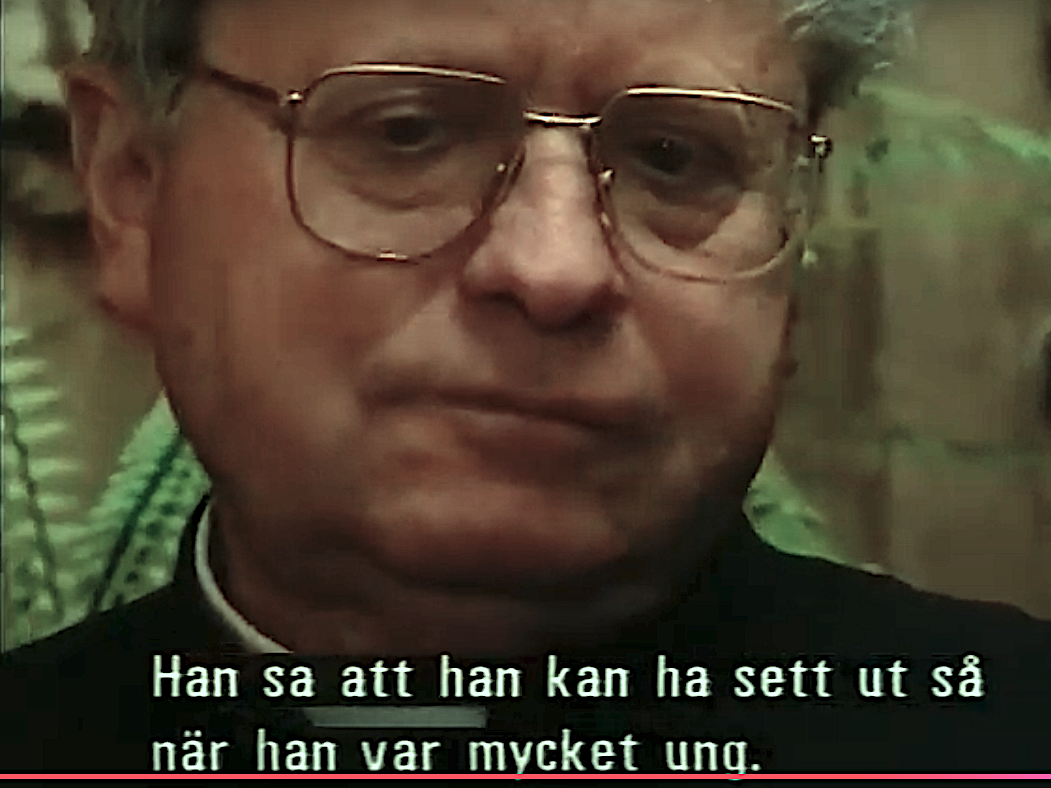

To get more clarity on the matter, the SVT team now trots off to the rector of the Anima seminary, Johannes Nedbal (1934-2002). The team tells him that they suspect that Kaminski is identical to Müller and shows a photo of the latter. The photo is a poor photocopy on a plain A4 paper. It is an old photo, and Müller is dressed in civilian clothes. The principal finds a certain resemblance to Kaminski whom he hasn't seen for perhaps 40 years and says it could be Kamin-ski.

But he says, Kaminski hardly looked like a Gestapo officer, but rather like a forest ranger from Steiermark. Funnily enough, the description fits quite well with the only 170 cm tall and ordinary Müller.

The headmaster first makes a spontaneous comment, questioning whether Kaminski was a particularly good Catholic. What may have been behind the comment remains unclear, but appar-ently the headmaster remembered something negative about Kaminski

.

But he is the only one who knows that the photocopy represents Müller. Principal Nedbal now asks Kaminski's successor as trustee, Arcangelo Speciale, if he recognizes Kaminski. After being hesitant at first, the trustee says emphatically, "Yes, he is," and says that he got to know Kaminski before he died. The camera captures how Principal Nedbal sulks and is silent for a moment. When he then translates the steward's unequivocal answer into German for Müller's daughter, he weakens the German translation: "He said he might have looked like that when he was very young." Principal Nedbal does not seem at all to like that Müller has actually been identified but does not yet reveal anything to the staff at the seminar.

Seminary staff are now providing more information about Kaminski. He is said to have hidden in the seminary as early as 1931 before the war to avoid military service, but it is not clear where he came from. After the war, he had worked for a film company but returned in the 1950s as an administrator at the seminary. He is also said to have been Hudal's driver. This information is difficult to reconcile with the pages of the book about Hundal’s grave, where Kaminski is said to have worked as a trustee for more than 40 years, i.e. already before 1933.

The Swedish TV team asks for photos of Kaminski and is referred to an elderly lady on the staff who must have photos at her home. They go there, but the lady cannot find a single photo of Kaminski. But the fact that the seminary would have had an employee from at least 1950 to 1973, perhaps even from 1931, without him appearing in a single photograph, is quite strange.

Surprised, the lady spontaneously tells the team that Kaminski did not exist in the social security system. This certainly shows that he was not registered with the Italian authorities!

Müller on the run in 1945

If Müller managed to get to Rome and changed his name to Kaminski there, how did he do it? How was he able to survive in Berlin after he and his collaborator Scholz left Hitler's bunker? One can only speculate. But he - if anyone - probably knew more secret ways out of Berlin than most.

The various stories about how he was found dead are partly contradictory, partly just stories.

That Müller, with his knowledge and resources in the form of loyal followers, may have laid false trails seems likely. None of those who claimed to have found his dead body had photo-graphed the body or face of the person they thought was Müller.

We also do not know how he could have contacted Hudal in Rome. If you search for the two's surnames together on the internet, you don't get a single hit. In the SVT documentary there is only one photo showing Müller with a possible Hudal in the background, namely from Hitler's grand visit to Rome in 1938. Although Hudal and Müller may not have known each other person-ally, they certainly must have known of each other. Their political profiles are quite similar: not full-blooded Nazis, but ardent Catholics, obsessed with hatred of Bolshevism.

Since Hudal was obviously one of the main characters of the Rat Line, no previous personal friendship was needed to help him hide. An example of this is Adolf Eichmann, who did not be-long to the group of South German or Austrian Catholic Nazis at all but had an Evangelical Lu-theran background. Nevertheless, he was taken care of by the Rat Line. According to one ac-count, he converted to Catholicism in return.

And since Müller was one of Europe's most best-informed people concerning secret organiza-tions and routes, he should have found it quite easy to contact Hudal. On his way to Rome, Mül-ler could safely hide in various monasteries and churches, because the Allies were discouraged from searching Catholic churches and monasteries!

Hudal admitted in his memoirs, written in 1962, that he had helped Nazis to escape. He called his protégés” so-called war criminals” who had fought against Bolshevism. He said his campaign to help them was a form of compassionate love. Hudal did not name names, but is believed to have helped Adolf Eichmann, Barbie - the Lyon murderer - and Josef Mengele, among oth-ers.

Final words

The SVT documentary was broadcast in 1995 and aroused surprisingly little interest. The program has not been available on SVT Play, probably for copyright reasons; some episodes are borrowed from sources that retained their copyright. However, the documentary can be traced on the Inter-net under the name “Min pappa var Gestapochef”. It is also available in the National Swedish archives, Riksarkivet in Arninge.

The person responsible for the documentary, Lars Weldeborn (b. 1952), hardly asserts that he has proved that “Kaminski” is identical with Gestapo-Müller. I find it extremely likely. Before dismissing his TV documentary as infotainment, one should try to answer the following ques-tions.

- Why did Müller's daughter receive some book pages about a bishop and who was in his grave, when she had actually asked the Vatican about Gestapo-Müller?

- Why did the Vatican historians not want to know more from her when she asked about the meaning of the book pages?

- Why was no one with “Kaminski's” personal data at the Austrian authorities?

- Why were there no photos or notes about “Kaminski” in the seminary's archives, even though he was supposed to have worked there for 40 years?

- Why was “Kaminski” not registered with the Italian authorities?

- Why did the seminary claim that “Kaminski” were Polish and called Kamienski?

- Why did “Kaminski's” daughter in Rome not want to be interviewed, and why did her husband threaten to sue SVT?

- Why did the manager of the seminary deny ever having met “Kaminski” even though he had said a few hours earlier that he had gotten to know him before he died, and had identified “Kaminski” in a picture of Müller, and moreover?

- Why did the seminar never send any documents to SVT that could prove that “Kaminski” really worked there for 40 years?

The viewer can decide for himself what he wants to believe.

But how could one prove - or disprove - that Heinrich Müller was identical to the administrator “Kaminski” in the Austrian seminary in Rome? Searching the mass grave in the old Jewish cemetery at Grosse Hamburger-strasse is not possible for Jewish religious reasons. And even if it were allowed, searching for Mül-ler's body in a mass grave among thousands of others would be like looking for a sewing needle in a haystack.

A more reasonable alternative would be to reopen Hudal’s grave and identify Müller's re-mains. With modern osteology, it would possible, but probably such an investigation would not be allowed by the Anima seminary.

But there is a more modern way to get to the bottom of things, namely with DNA samples. If Müller's descendants in Norway, or those in Germany where he had children, wanted to give their DNA, the riddle would probably be solved quite quickly - if Kaminski's descendants in Italy also agreed. A refusal on the part of the latter would still indicate that the documentary had most likely hit the mark.